Every time the wind changes, which is often here, Niko watches me from his spot on the rooftop wall. He lies there like a cat, flexing his feet and letting the sun warm his stomach, a cigarette resting between the index and middle fingers of his right hand. He watches me, waiting to see if, this time, the meltemi will pull me down to the harbour and out to sea again.

Every time the wind changes, which is often here, Niko watches me from his spot on the rooftop wall. He lies there like a cat, flexing his feet and letting the sun warm his stomach, a cigarette resting between the index and middle fingers of his right hand. He watches me, waiting to see if, this time, the meltemi will pull me down to the harbour and out to sea again.

That same meltemi brought me here two weeks ago. It can take you by surprise when you’re out in it, suddenly swirling up out of nowhere and blowing you off course, as if the gods themselves were up there playing water chess with you. Before coming here, I’d had to find shelter on a couple of the smaller islands, although never for more than a night.

The evening I came to Mykonos was different.

This time the wind was wilder and my little yacht, Skiouro, was having to work hard. I hadn’t wanted to stop off at Mykonos. Oh, it’s pretty enough, with its stack of sugarcube houses and warren of winding whitewashed alleys in the main town, but it gets so busy in the summer months that I had planned to avoid it. But the gods had different ideas and blew us in to port on that mischievous meltemi.

Niko says that just as the wind brought me here, it will take me away again. He’s right to worry. The truth is, I am finding it harder and harder to resist the pull. Each time the breeze picks up, I stop and breathe in deeply, my nose twitching like a dog catching a scent for the first time. I don’t even try and hide that I’m doing it any more. I can’t help what I am. I’m meant to be out at sea, not playing house with what was only meant to be a temporary diversion.

For the first day or so, I only ventured as far as the handcarts at the end of the quay. I bought oranges the size of melons, freshly-cut greens that looked more like weeds than any vegetable I knew and a couple of lemonade bottles filled with retsina. From the fishing boats coming in alongside me, I bought marides, or whitebait. I’d spend the rest of the day cleaning up Skiouro, taking the time to stow her ropes and sails properly and mending what the meltemi had damaged. Then, in the evenings, I would sit on deck with a plate of fried merides and greens, drinking a glass of retsina, listening to the boats rocking gently in the harbour, their clinking masts sounding like goats’ bells. I’d sit and watch the meltemi calm down, burnt out by one of those famous Aegean sunsets.

When I’d tidied and swabbed down everything I could and the wind outside the harbour walls was still no fairer, I decided to explore the island. At first, I stuck to the main town, wandering the maze of streets, being buffeted by tetchy tourists. Mykonos is a barren island and I had come ashore not inclined to find anything to like in my temporary home. But the more I walked through the whitewashed walls and streets, past the balconies and window boxes of geraniums, the weedlike spread of bougainvillea and clematis, the turquoise-blue shutters and doors, the more I came to like the place.

I admit that there were times when I felt I was drowning in the blinding whiteness of it all. All I had to do then was go and sit in a waterside taverna overlooking Little Venice and watch as the waves reached up to where the balconies hang over the sea. From there, I could walk up to the windmills and look out over the water towards Delos.

Just as the confusing web of streets draws you into the town, I found myself being sucked further inland and spending more time walking the hills, which is how I’d met Niko. We’d talked, and he’d laughed at my whispered Greek, although he still says that he wasn’t laughing at what I was saying. He’d just found it sweet that someone with eyes as blue as the Aegean was speaking his language. Or trying to. It’s cute, is what he’d said. We almost parted then and there. If there’s one thing I hate being called, it’s cute. But Niko can be very persuasive, and so I stayed that night. And the next. And here I am, still.

Niko shifts on the wall and raises himself up to rest on his elbow. He draws on his cigarette and I know he is watching me now. His face is in shadow but I can feel his eyes on me, making me shiver despite the morning sun.

I close my eyes and tilt my face to the sky, feeling the warmth stroke my forehead and cheeks. Then the meltemi brushes my hair away from my neck like a lover. I try and resist its pull but I sway a little and can hear Niko shift and sit upright. The wind is changing. The bells I hear are from the boats in the harbour, not the goats on the hillside, and down there somewhere amongst them is my little Skiouro waiting patiently for me.

It is time to leave, the wind is saying, time to move on. You belong with me, not him, you belong out there on the water. I open my eyes, see the light dancing on the waves like fireflies, and start to run. I think I hear Niko call out but I can’t hear what he says. His words are swallowed up by the wind. I don’t look back. I can’t. I’d stay, I know I would, and I don’t belong here. I’m running faster now, the wind at my back, all the way down the hill to the harbour. It’s time.

oh gosh I thought she’d stay with Nikos, but the tidal swell was just too great and out she goes again. Lovely story well told

Thanks Marc! Sadly, no happy ending for Nikos but it’s for the best, I think.

Quite a lovely story. Beautiful pacing and description.

Brings to mind the myth of a selkie, who must return to sea if it finds the pelt it shed to become human.

Well done.

Thanks so much, Marisa. I think I might have been playing with the selkie idea after the mention in last week’s story.

I enjoyed the opening decription of Niko being cat-like. You usually read details of lethargy, or female feline grace, not letting the sun warm your belly. You have some smart use of details here.

Thanks John. I appreciate that.

Mmmmm…. So beautifully evocative. You take us there, Kath, you really do. It’s fabulous and I’m waiting for your novel now

How many copies can I put you down for? 😉 Seriously though, thank you. That’s the effect I was hoping to achieve.

Yes, it’s another great story, Kath. So vivid, reads with the immediacy and colour of a diary. You can smell the salt, the wind, sense that whiteness. And then like a dream it’s all blown away. We arrive and we depart, with your heroine, on the fleeting wisps of the sky.

I keep saying I must do this Friday fiction thing but at present I’m just very busy at the day job and even now, Saturday, should be re-writing a children’s story ……about flying carpets as you ask……something else borne here and there on a mysterious current of air and from a place, dry and dusty, a long way beyond the summer depths of the blue Aegean.

Thanks Fennie. I wanted it to feel a real enough place but to have her almost whisked out of it.

One of my favourite childhood stories was E. Nesbit’s The Phoenix and the Carpet, and I loved One Thousand and One Nights, so I hope I get a chance to read your flying carpet story.

Another beautifully written story Kath, I have visited Greece many times, mostly Kefalonia, and your writing brings happy images to me. I have actually picked from the roadside, the wild weed-like vegetables that you mention, to cook in our friends’ house, to eat with the evening meal.

You capture the breath and atmosphere of Greece perfectly.

Thanks Steve, that’s a lovely compliment. I lived in Greece for a year and am very fond of the country and its people, so I was hoping to do it and them justice.

This is simply beautiful. The descriptions of the sea, her lover, and being pulled by the wind of the sea. Gorgeous writing!

Thank you, lovely lady. Appreciate that.

Beautifully told story. Excellent descriptions, and a very lyrical tone! The pull of the sea is persuasive indeed!

It’s always had a strange pull on me, although I’m not a great sailor. I think there might be a bit of wish fulfilment in this story! Thanks for reading, Icy, and lovely to see you over here.

Your story had a very poetic feel to it. I was drawn into your descriptions from the start and held there until the end. I also liked that opening description of Niko as a cat in the sun. It is a lovely retelling of a sailor at sea who enjoys their port of call but enevitable succombs to the pull of the sea (or in this case, the meltemi).

Thanks very much for your feedback, Alan, and for popping over to The Nut Press. Good to see you here.

Another lovely piece, Kath! So descriptive, as everyone else has said. I feel like I’ve just escaped!

Hoorah! I was hoping to take people there. Thanks Talli!

This is absolutely beautiful Kath, I felt like I was there.

Wonderful! Bring on the novel! xx

Oh wow! This is a beautiful story. Very well written and brilliant description. I’ve been to Greece and you capture it perfectly. It reminded me and makes me yearn to go back. I love the bit about the wind changing and it’s not the goats’ bells but the bells from the boats in the harbour. I also love how she gets up and runs without looking back.

Ooh, and Niko warming his stomach in the sun and flexing his feet, cat like.

I could go on and on… well done!

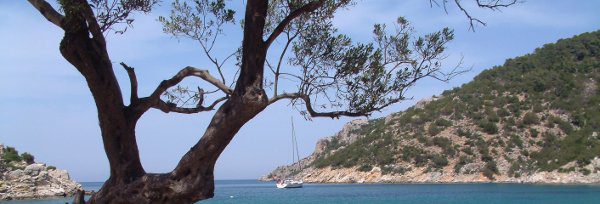

(stunning photo too!)